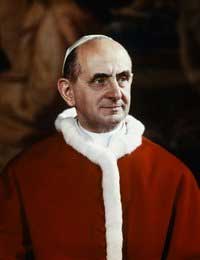

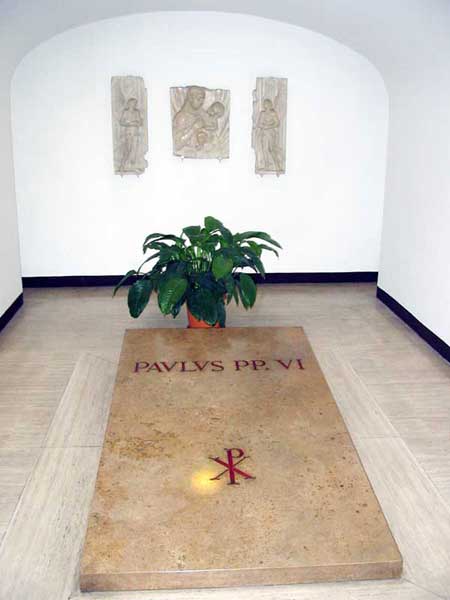

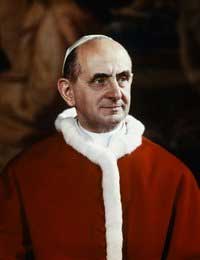

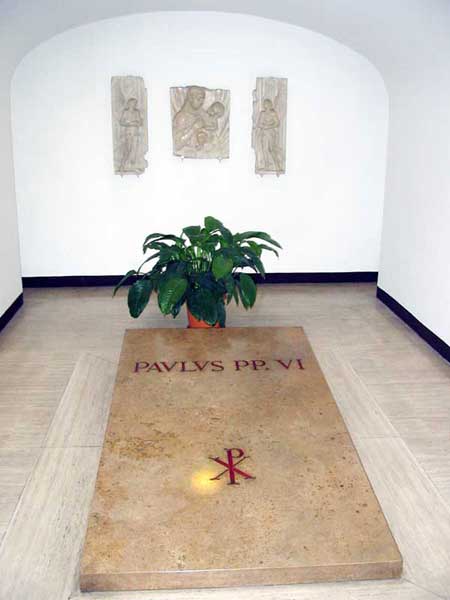

Pope Paul VI (Latin: Paulus PP. VI), born Giovanni Battista

Enrico Antonio Maria Montini (September 26, 1897 – August 6, 1978), reigned

as Pope and as sovereign of Vatican City from 1963 to 1978. He presided over

the Catholic Church during most of the Second Vatican Council and played a

central role in implementing its decisions.

Early career

Giovanni Montini was born in Concesio in Brescia province, Italy, of a

family of local nobility. He entered the seminary to train to become a

Catholic priest in 1916 and was ordained a priest in 1920. He studied at the

Gregorian University, the University of Rome and the Accademia dei Nobili

Ecclesiastici. His organisational skills led him to a career in the Curia,

the papal civil service. In 1937 he was named Substitute for Ordinary

Affairs under Cardinal Pacelli, the Secretary of State under Pope Pius XI.

When Pacelli was elected Pope Pius XII, Montini was confirmed in the

position under the new Secretary of State. When in 1944 the Secretary of

State died, the role was assumed directly by the pope, with Montini working

directly under him.

Some of his work during this period remains shrouded in mystery, with claims

and counter-claims, most notably concerning his involvement in the

diplomatic activities of the Vatican during the conflict. For example, the

Vatican's repeated contacts with Count Galeazzo Ciano, fascist Minister of

Foreign affairs and son-in-law of Mussolini, remains an issue of some

criticism. Montini, who worked as a diplomat, has been accused of having

obtained from the Fascists, at the beginning of the war, some promises of

uncleared advantages for the Vatican, in exchange of its eventual support.

However, many other historians dispute this analysis.

The unique complexity of the war-time period saw Montini procure large sums

of money to aid European Jews, while he is also alleged to have been

involved in enabling some leading Nazi officers to escape the collapse of

the Third Reich. Formally a simple administrative employee of the Vatican

government, but effectively the closest supporter of Pius XII, he has often

been recognised as one of the most important political figures of the

period. No official confirmation exists, but evidence indicates that he

(along with Alcide De Gasperi) attempted to set up a channel of

communication between Crown Princess Maria José (daughter-in-law of the King

of Italy and wife of the Prince of Piedmont, Umberto) and the United States,

in order to find a separate peace for Italy with the United States; the

Princess however was not able to meet Myron Taylor, President Franklin D.

Roosevelt's special representative to the Vatican, and no one knows if

Montini was unable to organise this meeting or unwilling to do so.

Archbishop of Milan

Montini was appointed in 1953 to the senior Italian church post of

Archbishop of Milan. Traditionally such appointment would be followed by

being made a cardinal at the next consistory (when vacancies in the College

of Cardinals are filled). To the surprise of many, Montini never received

the red hat (as the appointment to the cardinalate is often called) before

Pope Pius's death in 1958; what was not known was that at the Secret

Consistory in 1952 Pope Pius revealed that Montini had declined the

cardinalate. Though many viewed him as the person who would have succeeded

Pope Pius, since Montini was not a member of the College of Cardinals,[1]

Cardinal Angelo Roncalli was elected pope and assumed the name Pope John

XXIII. Roncalli almost immediately raised Montini to the cardinalate.

Pope

Montini was generally seen as Pope John's heir apparent. Montini was an

enthusiastic supporter of Pope John's decision to establish the Second

Vatican Council. When John died of cancer in 1963, Montini finally was

elected to the papacy, where he took the name Paul VI. He brought the Second

Vatican Council to completion in 1965 and directed the implementation of its

directives until his death in 1978. He was also the last pope to be crowned;

his successor Pope John Paul I abolished the ceremony during his reign,

though it could be reinstated. Paul VI donated his own Papal Tiara, a gift

from his former Archdiocese of Milan, to the Basilica of the National Shrine

of the Immaculate Conception in Washington, D.C. as a gift to American

Catholics. In 1965 he established the Synod of Bishops but controversially

withdrew two issues from its authority, priestly celibacy and the issue of

contraception and made both the subject of controversial encyclicals.

Humanæ Vitæ

Pope Paul's most controversial decision occurred on July 24, 1968, when

in his encyclical Humanæ Vitæ, "Of Human Life", he rejected the

recommendations of a commission established by John XXIII and reaffirmed the

Catholic Church's condemnation of artificial birth control. His decision was

unexpected, as many in the Catholic world expected the Church to accept with

some reservations the technological advances that had produced the

contraceptive pill. In subsequent decades, many Catholics opted to use birth

control in spite of church teaching. To its supporters, Humanæ Vitæ is seen

as a valued and welcome reaffirming of the sanctity of human sexuality and

the procreative act, unencumbered by a modern drift away from absolute to

relative concepts of morality.

A commission composed of bishops, theologians, and laity had been

established for the purpose of reviewing the teaching on birth control. It

was the commission's majority recommendation that the Church relax its

stance on birth control. Upon the receiving the commission's report, Pope

Paul made the highly controversial decision to disband the commission, and

not only ignored their recommendations, but did exactly the opposite and

with his Humanæ Vitæ encyclical reinforced the ban on birth control.

The encyclical gained further significance as the Catholic faithful began to

feel disenfranchised from the Church. Whereas in the past, the Vatican's

historical conciliarism provided checks and balances on the Pope's

authority, with Pope Paul VI's rejection and disbandment of the commission

these checks and balances of the past were swept away. The Pope's authority

in Church matters had became elevated to monarchical power.

As public opinion seemed to turn against the Pope, it was the last

encyclical of his papacy.

To its many opponents, Humanæ Vitæ is seen as a calamity akin to Pope Pius

IX's Syllabus of Errors, with the Church turning its back on technological

advances that could help humanity deal with the problems of serial births

and climbing birth rates, particularly in the Third World. External

observers noted that many lay Catholics reacted by moving towards the more

typically Protestant attitude that after listening to the Church's teaching,

they could judge for themselves what was sinful and what was not.

While Paul's successor, Pope John Paul I, in a meeting with United Nations

population experts during his short reign, did give some indication that

Humanæ Vitæ might be changed somewhat, Pope John Paul II unambiguously

supported the encyclical.

The Pilgrim Pope

Pope Paul VI became the first pope to visit five continents, and was the

most travelled pope in history to that time, earning the nickname the

Pilgrim Pope. In 1970 he was the target of an assassination attempt at

Manila International Airport in the Philippines. The assailant, a Bolivian

Surrealist painter named Benjamín Mendoza y Amor Flores, lunged toward Pope

Paul with a kris, but was subdued. Although the Vatican denied it,

subsequent evidence suggests Pope Paul did indeed receive a stab wound in

the incident.

Pope Paul became the second pope to meet an Anglican Archbishop of

Canterbury, Michael Ramsey, after the visit of Archbishop Geoffrey Fisher to

Pope John XXIII on December 2nd 1960. He was also the first pope for

centuries to meet the heads of various Eastern Orthodox faiths. Notably, in

1964 he met Patriarch Athenagoras of Constantinople and they rescinded the

1054 excommunications of the Great Schism and produced the Catholic-Orthodox

Joint declaration of 1965.

An Indecisive Pope?

According to some critics, Pope Paul VI was habitually indecisive.

One example of Paul's alleged indecisiveness revolved around his inability

to decide how to deal with the scandal-ridden American Cardinal Cody, who

was surrounded by allegations of financial and sexual impropriety. Cody even

invited his female 'friend' to pose in a picture with him and Pope Paul

taken when Cody was being awarded the red hat. Paul changed his mind over

whether to remove Cody, on one occasion contacting a Vatican official at

Rome Airport, whom he had sent to inform Cody of his dismissal, and telling

him to return as he had changed his mind. Cody remained in office until his

death.

Some critics point to Paul's response to Archbishop Lefebvre, who challenged

papal authority by refusing to accept the New Mass and liturgical reforms

produced by Vatican II. The pope summoned Lefebvre to meetings in which he

argued with Lefebvre and showed his great frustration, but he did not

excommunicate Lefebvre, as many had expected. Lefebvre was eventually

excommunicated automatically (latae sententiae) for his illicit ordinations

in 1988 during the reign of Pope John Paul II.

The pope's response to the critics of Humanae Vitae is also cited as an

example of indecisiveness. When Cardinal O'Boyle, the Archbishop of

Washington, D.C., disciplined several priests for publicly dissenting from

this teaching, the pope gave him encouragement. But when other bishops did

nothing to quell dissent, the pope raised no objection. And when bishops in

Canada, France, Sweden, and the Netherlands were lukewarm in their support

or even publicly expressed reservations about this teaching, the pope did

not discipline them in any way.

Some of Pope Paul's statements in the 1970s seemed critical of the direction

taken by the Church after Vatican II, expressing his dislike of some of the

"pedestrian" language used in some translations of the New Mass. But he did

not generally indicate such unhappiness in his public statements. He did

oppose Liberation theology after the 1962-65 Vatican Council, frowning on

the CELAM (Latin American Episcopal Conference) support to it.

According to some sources, as Paul became older he spoke of abdicating the

papal throne and going into retirement. Some critics see this as another

example of indecision, as he remained in the papacy until his death.

It is rumored that Pope John XXIII referred to then-Cardinal Montini as "Our

Hamlet" (Amleto), in reference to his indecisiveness. The private

secretaries of both popes have denied that John ever made such a statement.

Pope Paul himself reflected that description of himself in a private note

written in 1978. He asked:

What is my state of mind? Am I Hamlet? Or Don Quixote? On the left? On the

right? I do not think I have been properly understood.[2]

Controversial sermons

On June 29, 1972 Pope Paul VI in a homily delivered a strikingly

downbeat analysis of the state of the Roman Catholic Church post Vatican II.

He told a congregation:

We believed that after the Council would come a day of sunshine in the

history of the Church. But instead there has come a day of clouds and

storms, and of darkness ... And how did this come about? We will confide to

you the thought that may be, we ourselves admit in free discussion, that may

be unfounded, and that is that there has been a power, an adversary power.

Let us call him by his name: the devil.

His fears of satanic infiltration of the Church were even more pronounced in

a later sentence which is widely quoted by conservative Catholics. He said:

It is as if from some mysterious crack, no, it is not mysterious, from some

crack the smoke of Satan has entered the temple of God.

What he was alluding to was never explained. Some members of the

traditionalist movement have used that quote as a defense of their positions

on the direction the Church has taken following the council.

A few months before his death, Paul celebrated the solemn funeral of the

leader of Democrazia Cristiana, Aldo Moro (Moro was murdered by the Red

Brigades), who had sent him a famous letter from captivity. Moro and Montini

had been in the FUCI together, a Catholic association for university

students, many years before, and in time had become perhaps the two most

important Catholic figures in Italy.

Denial of homosexual rumours

Pope Paul VI caused considerable surprise in 1968 when, to the

consternation of his aides, he apparently denied rumours that he was

homosexual. Though rumours had circulated periodically in anti-papal and

anti-Catholic publications as to Paul's sexual orientation, with suggestions

of a past relationship while he was an archbishop with a priest who had

served as his secretary, when what Paul called the "scandalous rumours"

began to feature in some elements of the Italian media, he made the

controversial choice of issuing a public denial. It was the first time in

the modern era that a pope had commented in any way about his sexual

identity. [3] Controversy remains among historians as to whether the term

"scandalous rumours" actually referred to the Pope's sexuality, or various

other rumours concerning his papacy.

Footnotes

1 could still have become pope. In fact, at the 1958 election, Montini

did receive a couple of votes. But the cardinals in modern times invariably

elect a fellow cardinal to the post.

2 Cathal B Daly, Steps on my Pilgrim Journey (Veritas, 1998) p.

|